Until I started writing Blue Skies and Bench Space, I was horrendously ignorant about the history of molecular biology. Like everyone who did a PhD at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, I walked up and down staircases lined with photos of the great and the good, and shared a canteen with even more of the field’s superstars.

Sydney Brenner, Max Perutz and Aaron Klug were familiar features of the landscape, but while I could see they were brilliant and very alarming, I didn’t really know what Aaron had won his Nobel Prize for, or that Sydney was one of the fathers of molecular biology and had worked with everyone who was anyone. I did know about Max’s Nobel Prize, as I’d had some lectures on him when I was an undergraduate, but his habits of eating blackened bananas and never sitting down seemed far more interesting than his work as a crystallographer. In fact, during my four years at the LMB, I am sorry to say that my only interaction with any of them was when Max refused to sign a petition I’d got up to protest about sexist adverts in Nature, and Sydney asked me who I was in a lift. Pathetic. I wish I could say I was too absorbed in my highly complex work, but to be honest, I spent most of my work hours mindlessly sequencing DNA and analysing mRNA, and most of the rest of my time falling in and out of pubs.

Thanks to my wasted youth, when I began researching what eventually became Chapter 2 of Blue Skies and Bench Space, I uncovered a yawning gap in my knowledge. I knew that the work which had come out of the 5th floor of the Imperial Cancer Research Fund Labs (as the London Research Institute was known in those days) in the 1970s was terribly important, because everyone said so, but I had no idea why. My attempts to belatedly educate myself now comprise Chapter 1, which I hope will fulfill the same function for anyone else in the same boat.

Getting into the history of molecular biology has been one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever done. Like an amateur genealogist hunting for famous relatives, I got terribly excited when the penny suddenly dropped that the research I was going to write about at the ICRF was in a direct line of descent from the earliest attempts to study genes at the molecular level, and what was more, there were recordings of the pioneers of the field talking about their work. And what an amazing bunch they were! If you have a few minutes (or better still, hours!) to spare, take a trawl through the Caltech oral histories and the similar Cold Spring Harbor resource, and listen to Max Delbrück and his friends and colleagues talking about how they changed the molecular world.

My own particular favourite recording comes from a different, and even more beguiling source: Web of Stories is a treasure trove of recordings of the great and the good and the not so good, not just from science, but in just about any walk of life. Renato Dulbecco, who died in 2012 two days short of his 98th birthday, was interviewed in 2005 by Italian journalist Paola De Paoli Marchetti. The resulting videos are a total treat, partly because Dulbecco is impeccably elegant and very eloquent, but also because he speaks the most beautifully clear Italian I’ve ever heard (and was helpfully subtitled!). This was wonderful, as at the time I found the recordings, I was doing beginners’ Italian classes and had come to the conclusion that the only Italian I would ever understand was that spoken by my non-Italian fellow students.

Colonel James G Boswell, shingles sufferer and first funder of the eukaryotic molecular biology revolution

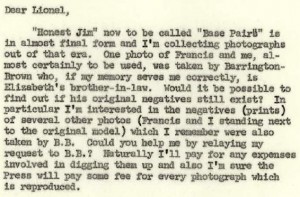

Disappointingly, when I checked on this potential relative with Lionel, he told me “The letter from Jim makes clear what he wanted from me and, as he says, “ if my memory is correct … “ In most cases it was, but not in this case.” Barrington-Brown, even though he was not related to Lionel’s wife Elizabeth, must have been contacted, as his photo appeared in The Double Helix, and went on to become one of the most famous science portraits in history. You can read about Barrington-Brown and how he came to be photographing Watson and Crick here. Sadly, the piece is one of the many obituaries that came out after he was killed in a car crash in 2012.

One person that I would have loved to have interviewed for Chapter 1, and indeed several other chapters, was the ICRF’s former Director Sir Michael Stoker, but it was not to be. By the time I got in contact with his family, Sir Michael was too frail to talk to me, and in August of this year, he too died at the age of 95. Of all the people who appear in Blue Skies and Bench Space, he alone commanded universal respect and affection in everyone who spoke about him. He was a very good scientist, a great Director who reshaped the ICRF into a world-class research environment, and by all accounts, a thoroughly nice man.

Discussion

No comments yet.