This blog is the first of what I hope will be a series. Over the next few weeks and months, I’ll be writing about the background to Blue Skies and Bench Space: the scientists I interviewed; the bits that didn’t make it into the final edit; the stories that were fascinating but too peripheral to include; some great audio clips (including an exclusive recording of Professor Sir David Lane eating sprouts), and my general musings on the challenges facing a failed academic starting a new mid-life career as a writer. Whilst the focus of most of the succeeding blogs will be the book, in this first article I’ve decided to write about myself, and how this whole project began. So, with apologies for self-indulgence, here goes:

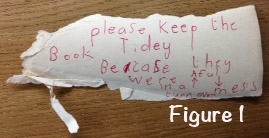

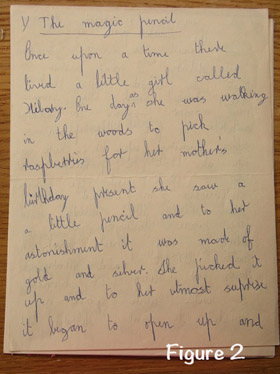

Like many people, in my heart of hearts, I always wanted to be a writer. I started young, composing stern messages directed at errant siblings (Figure 1) , and by the age of seven had progressed to fiction (Figure 2; further instalments available on request). Sadly for my literary aspirations, by the time I finished university, another career beckoned; after a PhD at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, I went off to San Francisco to work on the Myb oncogene with the wonderful Mike Bishop, returning to London in 1989 to start my own lab at the Institute of Cancer Research. For the next 20 years, I was a crossover molecular immunologist (shorthand for not knowing quite enough about either molecular biology or immunology, but hoping nobody noticed). How that part of my life went, and the reasons for my leaving bench science are described elsewhere, but suffice it to say, at the end of 2009, I was contemplating life outside academia with a mixture of relief and trepidation.

Like many people, in my heart of hearts, I always wanted to be a writer. I started young, composing stern messages directed at errant siblings (Figure 1) , and by the age of seven had progressed to fiction (Figure 2; further instalments available on request). Sadly for my literary aspirations, by the time I finished university, another career beckoned; after a PhD at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, I went off to San Francisco to work on the Myb oncogene with the wonderful Mike Bishop, returning to London in 1989 to start my own lab at the Institute of Cancer Research. For the next 20 years, I was a crossover molecular immunologist (shorthand for not knowing quite enough about either molecular biology or immunology, but hoping nobody noticed). How that part of my life went, and the reasons for my leaving bench science are described elsewhere, but suffice it to say, at the end of 2009, I was contemplating life outside academia with a mixture of relief and trepidation.

The first few months following my departure from “proper” employment were passed in a happy frenzy of self-improvement; I started learning Italian, upped my cello practice to several hours a day, got fit, lost weight, and saw my two children a lot more frequently. It was brilliant fun, but in the summer of 2010, when Ava Yeo of the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute (LRI) asked if I’d like to provide her with some short descriptions of important scientific discoveries made at her Institute, I jumped at the chance to start doing something less self-centred that would simultaneously give me an opportunity to work as a writer.

The first few months following my departure from “proper” employment were passed in a happy frenzy of self-improvement; I started learning Italian, upped my cello practice to several hours a day, got fit, lost weight, and saw my two children a lot more frequently. It was brilliant fun, but in the summer of 2010, when Ava Yeo of the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute (LRI) asked if I’d like to provide her with some short descriptions of important scientific discoveries made at her Institute, I jumped at the chance to start doing something less self-centred that would simultaneously give me an opportunity to work as a writer.

At this point, I need to come clean; the reason Ava asked me to write what eventually became the compilation of research milestones available on the LRI website was not that she’d heard of my literary prowess and had entered into a bidding war with sundry other research labs to engage my services. Rather, she knew all about me because I am married to the Director of the LRI, Richard Treisman. I was extremely uncomfortable about getting such a great offer as a result of my personal circumstances, but nevertheless, I took on the project as I thought I could do a decent job of it. All the years I’d spent as an active scientist had left me with a lot of contacts, and I’d been around for many of the major scientific advances that I was going to have to describe (although to be honest, I had generally failed to appreciate their importance at the time). Anyhow, it’s up to you to judge whether I did the right thing.

There was a compelling reason for the LRI’s interest in documenting its scientific highlights: in 2016, the lab will vanish as an entity, as it will be subsumed into the new Francis Crick Institute. The LRI, previously the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (ICRF) labs, has a proud, hundred-year history as a major research force in cancer and molecular biology, and it seemed important to mark its passing in some significant way. Having proved that I could string sentences together by writing the milestones, I got the go-ahead to embark on a much more ambitious memorial: the collection of science stories that have become Blue Skies and Bench Space.

From the start, I was very clear about what I wished to produce: a book that would be of interest to past and present ICRF and LRI staff, but that would also be engaging enough to attract people with no connections to the lab. I have a short attention span and an impatience with detail, so I wanted to make the stories as readable as possible for those endowed with similar butterfly minds. Simultaneously, I hoped to engage more serious brains by blending the gossip and personal details with some good solid science. I had no idea whether or how this would work, but began researching the first of my eight stories in spring 2011, with an interview with an old friend and colleague, Gerard Evan. Gerard’s major discovery, of the involvement of the MYC oncogene in programmed cell death, was made at the ICRF labs in the 1990s, and it seemed a good place to start, as I’d had a ringside seat. I’ll be telling you a bit more about Gerard in my next blogpost.

Discussion

No comments yet.